The Code Makers | By Alex Pearlman

The Code Makers

While some within biotech seek to decode life, others seek to create codes to live by. Jason Bobe and Alex Pearlman have worked on codes of ethics within Community Biology at different stages of its development. A decade ago, when the movement was still inchoate, Jason co-organized the “Continental Congress,” a meeting of community biology lab leaders to draft a shared set of values. These codes became the moral backbone of the nascent movement. Eight years later, when the movement had spread across the globe, Alex Pearlman led an effort to revisit these principles at the Global Community Bio Summit. Surprisingly, her group recast the earlier declarations as a set of questions. As biodesign emerges as a practice, does it require a code of ethics? And if so, what are lessons from the code makers?

We asked the same set of questions to Alex and Jason. Below is what Alex said. Click here to read Jason’s answers.

***

Alex Pearlman is an award-winning journalist and a bioethicist. She is a Research Affiliate at the Community Biotechnology Initiative at the MIT Media Lab, and a researcher in the Wexler Lab at the University of Pennsylvania, where she studies ethics and policy issues in Community Bio. She has been published in Stat, New Scientist, MIT Technology Review, Neo.Life, Vice, and elsewhere.

Biodesigned.

You’ve been developing codes of ethics in biology in one capacity or another for quite some time. What kinds of codes have you been working on?

Alex.

The most fun code I helped develop was a code for human augmentation technologies. A little over a dozen biohackers, ethics scholars, and body modification activists met at DEFCON in Las Vegas in 2019 with the express purpose of getting feedback on a draft code of ethics for self-directed human enhancement and augmentation.

The draft itself was already years in the making, but this particular meeting stands out to me as one of the best discussions on codes, ethics, independent research, and what designing the future might look like. We met in a private back room of the PF Changs at the Planet Hollywood Casino. There was red lighting, laughter, excitement and a demonstration of the PegLeg, an implanted device highlighting the real time urgency of the conversation at hand.

B.

Why are codes of ethics important to you and why should they be important to the rest of us?

A.

Codes of ethics communicate the shared values of a community and can act as a beacon for people who are aligned with the group’s values and might want to join. To me, a community should be able to point to something that simply states, “this is what we do and this is what we don’t do.” It can be the terms by which you hold your comrades accountable, and vice versa.

B.

You’ve helped develop a code of ethics for the Community Biology movement. What were your influences in developing the code, and what surprised you in their creation?

A.

The most surprising thing for me was that the document we developed at the Global Community Bio Summit in 2019 didn’t resemble a code at all. Instead, the Ethics Document 1.0 is a choose-your-own-adventure-style activity. It prompts the user to think critically about the ways they can produce ethical work. It’s interactive and much more personal than the average code of ethics, which is usually stagnant and boring. This also means that two groups using the Ethics Document to make their own codes might end up with radically differing results! But, that’s what makes it special and what I think makes it work for community biology.

B.

As technology evolves, how often should a code of ethics be reconsidered and revised?

A.

This is a tricky question, because some technologies are evolving faster than others! I think annual reconsideration of a code is too often and every decade is too long. So the sweet spot is probably between three and seven years, depending on the growth of the community and the pace of changes in technology.

Cite This Essay

Pearlman, Alex. “The Code Makers.” Biodesigned: Issue 9, 11 November, 2021. Accessed [month, day, year].

Americans Deserve A Bioethics Commission | By Alex Pearlman

When I close my eyes and dream of what’s possible for the new US administration, I imagine a lot of changes. In many ways, the dismantling of norms of the American establishment has created an opportunity to look forward, and reimagine ways to make it even better than business as usual. One of the major changes I imagine is a new, independent body within the government that deals specifically with the many nuanced ethical issues emerging with biotechnology and medicine.

I imagine a bioethics commission that stands apart from whoever happens to sit in the White House. It would be an independent body, like, say, the Federal Communications Commission, whose leadership is appointed by the president and approved by Congress. Recommendations from this bioethics commission could work on their own timeline, insulated from the news cycle and without being beholden to political theater.

I believe that if such a body had already existed, it would have buffeted the nation against the politicization of the coronavirus, offered a counterweight to the bungled response, and could have saved lives. And I believe it could help prepare the American public for the slew of ethical debates we face as trends in biotech, healthcare, and social justice come to a head.

Putting forward the dream of a new commission may sound far-fetched, but it’s not, actually. Other countries have freestanding bioethics councils housed within ministries of health. Or in the United Kingdom, for example, the Nuffield Council on Bioethics stands independently and works with Parliament and the public British public to parse bioethical issues.

In the US, bioethics is decentralized. There are groups within nongovernmental organizations like the National Academies of Medicine, centers for academic scholarship such as the Hastings Center. The National Institutes of Health have their own bioethics group.

There have also been presidential and congressional bioethics councils made up of clergy, scholars, and interested lay people who debate critical issues in medical research and emerging technologies, but these have been flawed. They convene to advise on a particular matter at the behest of the governmental branch, and just as quickly disband after they report back, or the president’s term ends.

The presidential commissions on bioethics serve at the pleasure of the president and advise on how we might regulate (or consider regulating) ethically murky terrain in the biosciences. Previous commissions have authored reports on brain death, embryonic stem cells, synthetic biology, research using human subjects, and other topics.

Over the last 50 years, these bioethics councils have offered a mixed bag of advice that often reflects the interests and politics of those who commission them. For example, the Obama Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues delivered ten projects, many of them highly useful, including one on advances in neuroscience. The George W Bush-appointed Council on Bioethics took an extreme position on stem cell research.

Congress has also set up a few of its own commissions, with varying results, including the failed 1988-1990 Biomedical Ethical Advisory Committee. The group had only two meetings before getting stuck on abortion issues and running out the clock on their funding without writing any reports.

It surprised no one that Trump failed to commission a bioethics council at all. Thankfully.

Ultimately, I think we need a bioethics commission that reflects a 21st century American public, that can set its own agenda, and be ready to spin out expert working groups to take up urgent issues, or organize longer term projects to advise on developments that emerge over decades.

We face many urgent issues, specific problems that require expert input and a quick turnaround because technology is moving swiftly and regulations are lacking. Topics might be artificial intelligence in hospitals, guidelines for minimum levels of pandemic preparedness, or repeat issues like the nuance of stem cell research. These groups would be empowered to recommend specific action to Congress or other regulatory bodies, including within the private sector, so that new technologies could be responsibly considered as they emerge without impeding innovation.

On the other hand, longer-term problems call for a different strategy. The US faces deep and complex issues of justice in biomedicine. The commission should be convened to deliberate on topics that have bearing on the long-term future and that require an interdisciplinary lens and strategic thinking, such as pharmaceutical pricing, medical deserts, and genetic engineering of human embryos.

A standing body can build trust over decades, as opposed to presidential-appointed commissions, which have the default position of being inherently politicized. Trust enables a standing body to shoulder moral responsibility for the difficult choices lawmakers must make, but which are sometimes unpalatable for elected officials constantly embattled in the 24/7 election cycle. By putting trust and responsibility elsewhere, Congress and the president can allow a commission to enact real progress.

The commission would also be responsible for education and outreach on the issues. We desperately need a group of experts to parse bioethical issues and translate them into popular culture. Bioethicists have a responsibility to lead the conversation about our biotech future.

We can fix the crisis of distributive justice in our health system, but not with the tools we have now. Maybe this is all a fever dream from the stress of the election, but when I close my eyes, I can see us doing better.

Special thanks to:

Holly Fernandez Lynch, University of Pennsylvania

Craig Klugman, DePaul University

Kayte Spector-Bagdady, University of Michigan

Elisa Eiseman, UK Science and Innovation Network

Dov Fox, University of San Diego

Cite This Essay

Pearlman, Alex. “Americans Deserve a Bioethics Commission.” Biodesigned: Issue 4, 23 November, 2020. Accessed [month, day, year].

The Folly of DIY Vaxxers | By Alex Pearlman

This past April I received a call from an acquaintance who said that he and five other scientists were cooking up their own Covid-19 vaccine.

He had access to a private lab in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and had already tested the vaccine on himself—twice.

I told him that I was surprised because I had always thought of him as a company man. He said he had never been motivated to be a “weird biohacker type.” With access to the best scientific equipment and research funding, he had never needed to be. But things were different now with the pandemic. He was worried about his aging parents and his high-risk friends dying. “If we do nothing, we are doing an enormous amount of harm,” he said. He was adamant that he was racing against time.

I was originally intrigued by the idea of a do-it-yourself (DIY) vaccine, and felt hopeful for the team that would soon be known as RaDVaC. But now I feel terrified. Something has shifted as the weeks have slogged on. At least four groups have independently claimed to have developed their own vaccines, which they’ve administered to themselves and their friends without any external validation or approval from the Federal Drug Administration. These include self-proclaimed biohackers, a medical doctor, and my acquaintance’s collective of Harvard and MIT scientists at RaDVaC.

Whether or not they’re qualified to develop vaccines, there’s something deeply disturbing about producing homebrewed Covid vaccines. I have a sinking feeling that someone is going to get hurt (or worse), and that these vaccines could undermine public faith in science and vilify the community biology movement, of which I’m a part. In the face of the federal mismanagement of the pandemic, these projects go beyond being selfish and elitist; they’re dangerous.

Many DIY vaxxers see themselves in league with movements such as Right to Try, which led the campaign behind a law signed by Donald Trump in 2018 that allows terminally ill patients to circumvent the lengthy FDA approvals process and try experimental or unapproved treatments. Today, advocates for body autonomy and biohackers have misinterpreted the concepts behind Right to Try to extend to experimentation on those who are healthy—in particular during this time of crisis.

Josiah Zayner, a self-proclaimed biohacker and activist, has argued that if terminally ill patients should be able to choose their course of care, DIY-ers should as well. "I see everyone constantly enslaved to our shitty scientific and medical system. We are told what we can and can't do to our bodies and what drugs and medications are acceptable for us to use,” Zayner wrote on Facebook in July. “The system has created gatekeepers to only allow those worthy to participate.”

Zayner gained notoriety in 2017 by injecting himself onstage at a biotechnology conference with a homemade CRISPR gene therapy.

For my own part, after a decade as a human rights and politics reporter and five years studying bioethics and health policy, I actually strongly believe in self-experimentation and in biohackers’ right to autonomy. I believe that the disruption that would come from community biologists DIYing their own medicines could be instrumental in reshaping the unjust US healthcare system.

But not right now. Rather than a humanitarian effort in the face of crisis, those creating vaccines for small groups or those who can pay (like the doctor who has been asked by the FDA to cease prescribing $400 vaccines) only serve to exacerbate the grave healthcare inequalities in this country.

“These groups are not going to do anything for the rest of the world. It’s just an ego trip,” Jeantine Lunshof, a bioethicist at Harvard Medical School, told me. Although she works side-by-side with George Church, one of the collaborators on RaDVaC, she is furious about these projects. I am too.

There is a fundamental difference between combating a pandemic and doing everyday self-experimentation. There are no pipelines for mass production of DIY vaccines, nor do these groups intend to make one. At best, these vaccines can be made in small batches, only available to the privileged few who are looped in or those who can pay for it. Meanwhile, the majority of those who most need access to a vaccine (frontline and essential workers, including low income and low wage workers) will be unable to access a DIY version. This lack of concern for others runs contrary to the ethos of community biology and open science movements. Rather than democratizing access to health technology, they’ve made it a fully elitist enterprise.

And what if these vaccines hurt people? “We can have casualties,” Lunshof told me, fearful that DIY creators or copycats might actually try to prove the efficacy of their drugs by purposefully exposing themselves to Covid-19. The RaDVaC team has already reached out to community labs around the globe seeking collaborators—it would only take one injury to set back the entire community biology movement.

Most importantly, combating anti-vaxxers and misinformation about the virus is just as crucial to public health as therapies and vaccines. If something were to go wrong, anti-vaxxers and those skeptical of science would brandish it as evidence against mainstream science. The fact that members of the RaDVaC team are affiliated with Harvard and MIT, and Zayner was previously employed at NASA, would only fuel the misinformation and anti-expert sentiment peddled online.

While self-experimentation can sometimes be seen as acceptable in scientific research and often legitimate in performance art, in this case it’s a mistake. The stakes are too high. DIYers should be more concerned about the downstream negative effects their actions could have than they are about circumventing established research pipelines in the name of body autonomy. The DIYvaxxers should sit this one out.

Share

References

Regalado, Antonio. “Some scientists are taking a DIY coronavirus vaccine, and nobody knows if it’s legal or if it works.” MIT Technology Review, July 29, 2020.

Murphy, Heather. “These Scientists Are Giving Themselves D.I.Y. Coronavirus Vaccines.” The New York Times, September 1, 2020.

Heidt, Amanda. “Self-Experimentation in the Time of COVID-19.” The Scientist, August 6, 2020.

Kofler, Natalie & Françoise Baylis. “Ten reasons why immunity passports are a bad idea.” Nature vol. 581, 379-381 (2020) doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-01451-0

Evans, Barbara J. “Minding the Gaps in Regulation of Do-it-Yourself Biotechnology.” 21 DePaul J. Health Care L. (2020)

Kofler, Natalie & Alex Pearlman. “COVID-19 Immunity Passports and DIY Vaccines.” Video recording of Genetic Engineering and Society Center Colloquium.

Pearlman, Alex. “Biohackers are using CRISPR on their DNA and we can’t stop it.” New Scientist, November 15, 2017.

Cite This Essay

Pearlman, Alex. “The Folly of DIY Vaxxers” Biodesigned: Issue 3, 17 September, 2020. Accessed [month, day, year].

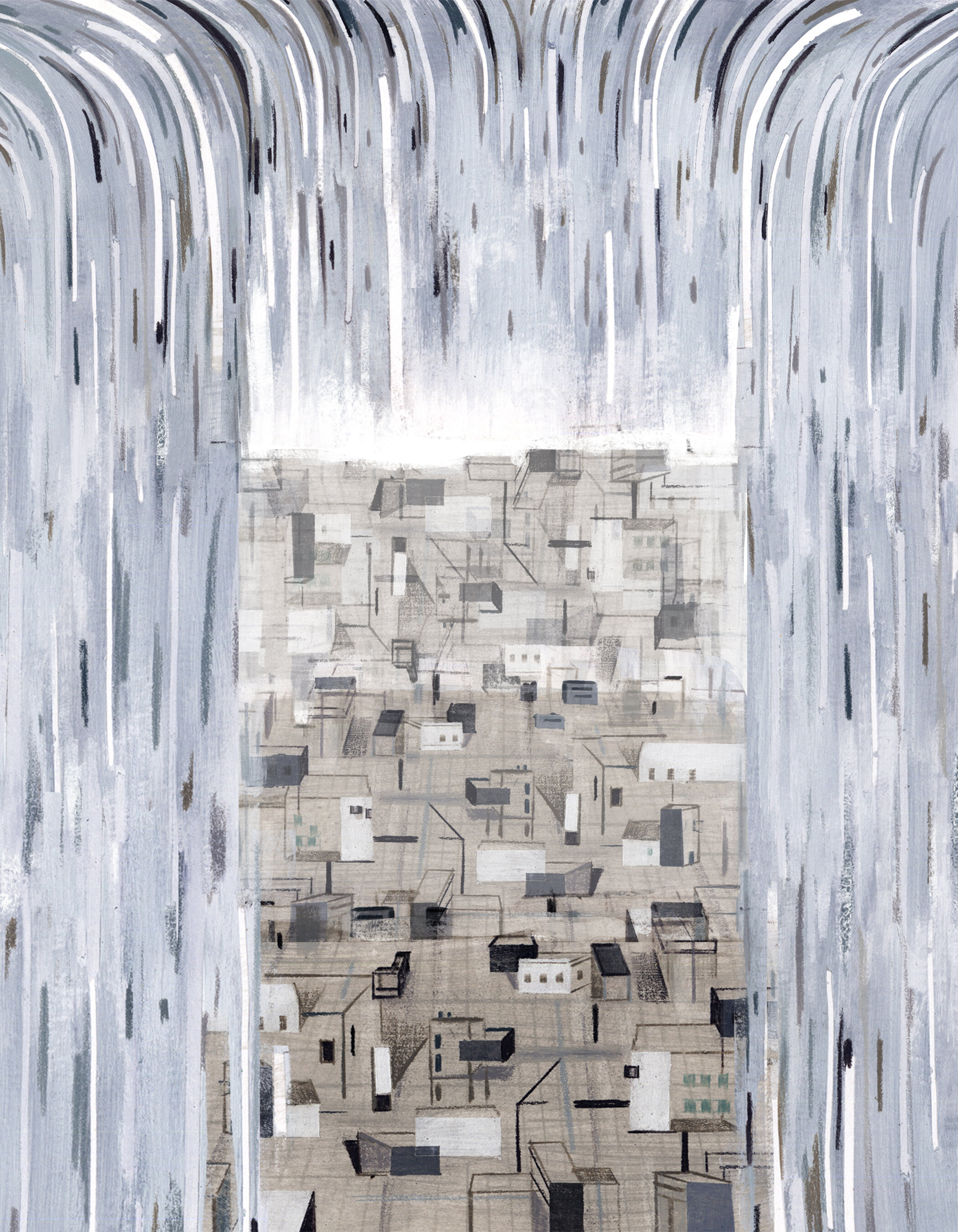

Can We Recycle Cities? | By Alex Pearlman

When I sit down in the playroom with my toddler to build a city, we use a classic set of wood blocks.

There are tall and short rectangles, squares, triangles, and cylinders that make excellent columns. Together we build fantastical arches and towers. I usually only get to admire the work for an instant before it all comes tumbling down with the ferocity of a three-year-old’s fist. And then we do it all again, using the exact same blocks.

If only this was how building construction really worked. Instead, when you tear down a building, 90 percent of it ends up in a landfill. Construction and demolition waste is the biggest contributor to landfills in both the United States and Europe [1][2]. The result is not just an architectural shame but an environmental tragedy.

But what if buildings could be recycled just like my kid’s cityscape? In a 10,000 square foot barn in Cleveland stands a heavy steel apparatus that looks a lot like a medieval torture device. It’s part of a system invented by architect Christopher Maurer called the Biocycler that turns construction debris into wood-like bricks and panels by binding it with mycelium, the root-like structure of mushrooms.

Imagine you’re a piece of lumber from a Victorian-era Midwestern home that has just been demolished. Instead of heading to a landfill, you are hoisted into a wood chipper that turns you into sawdust. You are then steam treated and seeded with mycelium, which grows all around you and binds your sawdust fibers together. As this damp mixture dries, you take shape: bricks, panels, or other forms. Finally, you are cooked at 100 degrees Celsius, like a loaf of bread. When you come out of the oven, you are pressed into a biomaterial, ready for use in a new building.

“Fungus is famous for bringing life from death,” says Maurer, founder of Redhouse Architecture, from inside the barn he and his team transformed into a hybrid design studio, industrial grow house, and manufacturing plant. “We’re continuing to find ways that this is superior to common building materials.”

Mycelium can play roles that would ordinarily require multiple materials in a traditional building. The bricks are strong enough to bear loads like cinder blocks, insulate like fiberglass, and withstand fire like gypsum.

In the 1970s, Swiss architect Walter Stahel suggested the concept of circular economies, or loops of “reuse, repair, and remanufacture,” to reduce waste from consumer products, including buildings [3]. By the time Michael Braungart and William McDonough published Cradle to Cradle in 2002, a small but growing group of architects had been trying to make the building industry more circular and focused on reducing waste [4].

In 2015, Copenhagen-based 3XN Architects proposed how new highrises could be built on the core of older buildings, preserving their existing structure rather than tearing them down. All new components would be modular and built to be readjusted and shuffled as offices turned into apartments, or taken apart and used again for entirely new purposes [5].

“We talk about buildings as material banks,” says 3XN’s founder Kasper Guldager Jensen. “You can think of buildings as a resource center with intrinsic value. And when you have to take a building down, you actually see it as valuable.” 3XN has so far completed one concept building and has a handful in development.

Maurer’s idea may be even more radical: attempting to use demolished buildings as fodder for mycelium. Architects have been trying to use mycelium as a building material since artist Phil Ross developed the concept of mycotecture as early as 2009. Ross built pup tent-sized arches of mycelium bricks for museum exhibitions. Visitors could sip tea from mushrooms growing on the installation. A few years later, Ecovative Design, a mycelium products company, designed its own mycelium insulation, an attempt to prove that cradle-to-cradle circularity could work in construction [6]. Finally, when David Benjamin won the Museum of Modern Art’s Young Architects Program in 2014 for a project to create mycelium towers over the courtyard at MoMA PS1, a trend had been set.

Sometimes called “nature’s glue,” advocates see mycelium as the Swiss Army knife of sustainable design, because it can be grown from agricultural and industrial byproducts and can make bricks, packing foam, furniture, and even leather.

Maurer was inspired after working for four years in Malawi and Rwanda for studioMDA and Mass Design Group to build affordable, sustainable housing in limited resource areas. When he came home to Cleveland in 2013, he thought that perhaps the grand idea he was chasing in Africa—using recycled, local materials to build new buildings—could also combat the housing crisis in suburban America.

Much of the area around Maurer’s studio never recovered from the 2008 recession. Homes across Ohio have been abandoned, foreclosed, or left empty, rotting, and unsafe. In eight cities across the state, over 41,000 homes will need to be demolished before 2021 as part of a national strategy for rebuilding the nation’s cities, according to the Brookings Institution [7].

“There are always going to be these homes that need to be demolished, so the goal is to put them to good use,” Maurer says.

Still, recycling demolished buildings into new materials has a long way to go. First, there is the basic life cycle analysis with regards to the costs of water, time, and energy of recycling a building with mycelium. Second, there are the safety hurdles. Construction materials are heavily regulated by the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM), an international group that standardizes construction specifications, practices, and test methods. Construction products must undergo strenuous weather tests, fire tests, smoke tests, rot and mold tests, and breaking tests, all using professional equipment and standardized environments. These tests are prohibitively expensive for small firms like Redhouse.

While Mauer waits for the US construction industry to catch up, he has turned his attention back to Africa. He is partnering with the government of Namibia and the MIT Center for Bits and Atoms to build a community of mycelium dwellings in a region called Brakwater. It’s a proof of concept for mycelium architecture. It also creates a double circular economy by allowing farmers to cultivate mushrooms generated from the building process for food.

With his latest project in mind, Maurer dismisses the high hurdles for mycelium buildings in his hometown. “It’s futuristic, maybe,” he admits. “But how hard can it be to recycle a house?”

Share

[1] “Sustainable Management of Construction and Demolition Materials.” EPA, Environmental Protection Agency, 26 May 2020, www.epa.gov/smm/sustainable-management-construction-and-demolition-materials.

[2] EU Construction and Demolition Waste Protocol and Guidelines. 4 Oct. 2018,

ec.europa.eu/growth/content/eu-construction-and-demolition-waste-protocol-0_en.

[3] Stahel, Walter R., and Reday-Mulvey Geneviève. Jobs for Tomorrow: the Potential for Substituting Manpower for Energy. Vantage Press, 1981.

[4] McDonough, William, and Michael Braungart. Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things. Vintage, 2002.

[5] Guldager Jensen, Kasper and John Sommer. Building a Circular Future. GXN, 2015.

[6] Hook, Susan Van. “Testing the Viability of Agricultural Byproducts as a Replacement for Mineral Particles in a Novel, Low Embodied Energy, Construction Material.” EPA, Environmental Protection Agency, 22 Oct. 2009, cfpub.epa.gov/ncer_abstracts/index.cfm/fuseaction/display.abstractDetail/abstract/8953/report/F.

[7] Mallach, Alan. Laying the Groundwork for Change: Demolition, urban strategy, and policy reform. Brookings Metropolitan Policy Program. September, 2012.

Cite This Essay

Pearlman, Alex. “Can We Recycle Cities?” Biodesigned: Issue 2, 16 July, 2020. Accessed [month, day, year].

Community Bio Confronts A Pandemic | By Alex Pearlman

As the movement mobilizes to face coronavirus, can it be trusted?

It’s evening in Bratislava, Slovakia, and Adam Krovina sits in his apartment peering into his webcam. The 31-year-old electronic engineer tells me about spending his nights and weekends on a new initiative that has connected hundreds of makers and amateur researchers around the world: building open source, affordable ventilators.

Krovina leads one of a handful of projects that have been awarded funding from Just One Giant Lab (JOGL), a French open source research platform that delivers microgrants to interdisciplinary teams working on community biology projects. Forced to hunker down in the aftermath of Covid-19, makers and community biologists have jumped into action, looking for ways to help.

Breezy, the low-cost ventilator and Android app system Krovina has created with a team of 15 other researchers, is just one of the many community-led projects kicking off around the world. With an uneven response from governments and overloaded health systems and ICUs, the crisis has created an opportunity for the DIY community to step in with unconventional solutions.

“It’s mind-blowing,” said JOGL founder Thomas Landrain from his home in Paris. “We are drawing a third path between academia and the corporate world where open and participatory science can happen.”

Community biology networks are strong, global, and have been in place for over a decade. When the pandemic began, these networks quickly pivoted to Covid-19 projects and opened their doors to anyone who wanted to help. Combined with an ethos of openness and the impulse to do something—anything—thousands of people are joining or starting DIY projects. The JOGL community has leaped from a couple-dozen people in February to 4,500 this month.

At a recent weekly Zoom meeting, 60 amateur researchers shared details about their projects and discussed ways microgrants (provided primarily by the AXA Research Fund) can be allocated by submitting projects to a community vote. So far, 15 projects have acquired funding that ranges from a couple hundred to a couple thousand euros.

The Covid-19 pandemic has created a situation where, for the first time, independent biologists face the very real potential that their projects could see use on the frontlines of a global public health emergency.

Some projects, including the Open-Source Low-Cost Syringe Pump, are being validated for safety and effectiveness by nurses at the Assistance Publique Hôpitaux de Paris, the largest hospital system in Europe.

Combined with an ethos of openness and the impulse to do something—anything—thousands of people are joining or starting DIY projects.

One JOGL-funded project, “Optimizing the NEB LAMP Test,” led by Aanika Biosciences in New York and BioBlaze Community Lab in Chicago, includes a microbiologist working at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The CDC researcher asked not to be named in this piece. The group says they hope to see their DIY diagnostics approved for general use after testing on patient samples at the CDC.

This all sounds exciting—and it is. But regulatory approval for these projects is not a foregone conclusion. The process to validate these tests is extraordinarily detailed, and without the kind of accreditation offered by the national laboratories, scientists involved worry that tests coming from amateur groups could do more harm than good.

“The reality is that if you’re working on something that results in clinical or life and death decisions, you’ve got to have some way of knowing that you’re right,” said Paul Freemont, head of Structural and Synthetic Biology at Imperial College in London and a longtime supporter of the DIYbio community.

The main concern with any DIY therapeutic, diagnostic, or device will always be safety and accuracy. A ventilator, for example, despite being a relatively unsophisticated piece of machinery, must include a sensitive gauge that can accurately monitor the pressure on a patient’s lungs. Otherwise, it could injure or even kill someone, said Russell Buhr, a pulmonary and critical care physician at UCLA.

“Would we love to know that there’s a reserve of thousands of ventilators that we could deploy if things got really hairy? Absolutely,” he said. But, he added, “We don’t want people wasting their time making something we can’t use.”

On the other hand, DIYers believe their projects should be taken seriously. “I know all of this is best explored by professional researchers and public health experts. But it seems to me like there may still be a role for biohackers,” Rick Byers, a software engineer and DIYer, wrote to the DIYBio message board on April 25.

Byers developed his own testing kit using qPCR from home in Ontario. When we spoke over the phone, Byers said that given the lack of resources for testing asymptomatic people, he hopes his test could be validated and used by public health officials to serve his local community.

“I’ve got 144 Covid test kits sitting right here,” said Byers, who lives near a long-term care home. “I could just go drop this off down the street.”

Share

Cite This Essay

Pearlman, Alex. “Community Bio Confronts a Pandemic.” Biodesigned: Issue 1, 6 May, 2020. Accessed [month, day, year].